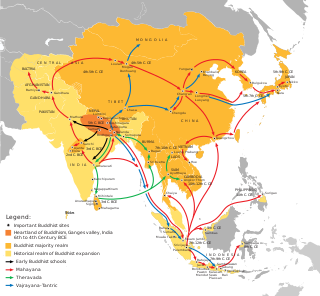

Buddhist expansion, from Buddhist heartland in northern India (dark orange) starting 6th century BC, to Buddhist majority realm (orange), and historical extent of Buddhism influences (yellow). Mahayana (red arrow), Theravada (green arrow), and Tantric-Vajrayana (blue arrow).

The

history of Buddhism spans from the 5th century BCE to the present; which arose in the eastern part of

Ancient India, in and around the ancient Kingdom of

Magadha (now in

Bihar,

India), and is based on the teachings of

Siddhārtha Gautama. This makes it one of the oldest religions practiced today. The religion evolved as it spread from the northeastern region of the Indian subcontinent through

Central,

East, and

Southeast Asia. At one time or another, it influenced most of the Asian continent. The history of Buddhism is also characterized by the development of numerous movements, schisms, and schools, among them the

Theravāda,

Mahāyāna and

Vajrayāna traditions, with contrasting periods of expansion and retreat.

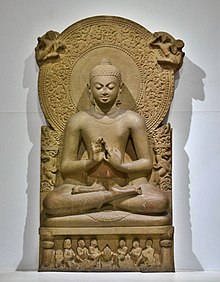

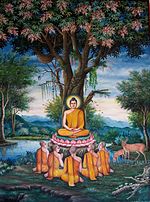

Life of the Buddha[edit]

The Buddha giving sermon to his followers at Sarnath, India.

After an early life of luxury under the protection of his father, Śuddhodhana, the ruler of Kapilavasthu which later became incorporated into the state of

Magadha, Siddhartha entered into contact with the realities of the world and concluded that life was inescapably bound up with suffering and sorrow. Siddhartha renounced his meaningless life of luxury to become an

ascetic. He ultimately decided that asceticism couldn't end suffering, and instead chose a

middle way, a path of moderation away from the extremes of self-indulgence and self-mortification.

Under a fig tree, now known as the

Bodhi tree, he vowed never to leave the position until he found

Truth. At the age of 35, he attained

Enlightenment. He was then known as Gautama Buddha, or simply "The Buddha", which means "the enlightened one", or "the awakened one".

For the remaining 45 years of his life, he traveled the

Gangetic Plain of central

India (the region of the

Ganges/Ganga river and its tributaries), teaching his doctrine and discipline to a diverse range of people. By the time of his death, he had thousands of followers.

The Buddha's reluctance to name a successor or to formalise his doctrine led to the emergence of many movements during the next 400 years: first the schools of

Nikaya Buddhism, of which only

Theravada remains today, and then the formation of

Mahayana and

Vajrayana, pan-Buddhist sects based on the acceptance of new scriptures and the revision of older techniques.

Followers of Buddhism, called

Buddhists in English, referred to themselves as

Sakyan-s or

Sakyabhiksu in ancient India.

[2][3] Buddhist scholar Donald S. Lopez asserts they also used the term

Bauddha,

[4] although scholar Richard Cohen asserts that that term was used only by outsiders to describe Buddhists.

[5]

Early Buddhism[edit]

Early Buddhism remained centered on the Ganges valley, spreading gradually from its ancient heartland. The canonical sources record two councils, where the monastic Sangha established the textual collections based on the Buddha's teachings and settled certain disciplinary problems within the community.

1st Buddhist council (5th century BC)[edit]

The first Buddhist council was held just after Buddha's

Parinirvana, and presided over by Gupta

Mahākāśyapa, one of His most senior disciples, at Rājagṛha (today's

Rajgir) during the 5th century under the noble support of king Ajāthaśatru. The objective of the council was to record all of Buddha's teachings into the doctrinal teachings (

sutra) and

Abhidhamma and to codify the monastic rules (

vinaya).

Ānanda, one of the Buddha's main disciples and his cousin, was called upon to recite the discourses and Abhidhamma of the Buddha, and Upali, another disciple, recited the rules of the

vinaya. These became the basis of the

Tripiṭaka (Three Baskets), which is preserved only in

Pāli.

Actual record on the first Buddhist Council did not mention the existence of the Abhidhamma. It existed only after the second Council.

2nd Buddhist council (4th century BC)[edit]

The second Buddhist council was held at Vaisali following a dispute that had arisen in the Saṅgha over a relaxation by some monks of various points of discipline. Eventually it was decided to hold a second council at which the original Vinaya texts that had been preserved at the first Council were cited to show that these relaxations went against the recorded teachings of the Buddha.

Aśokan proselytism (c. 261 BC)[edit]

The Maurya Empire under Emperor Aśoka was the world's first major Buddhist state. It established free hospitals and free education and promoted human rights.

Great Stupa (3rd century BC), Sanchi, India.

The

Mauryan Emperor

Aśoka (273–232 BC) converted to Buddhism after his bloody conquest of the territory of

Kalinga (modern

Odisha) in

eastern India during the

Kalinga War. Regretting the horrors and misery brought about by the conflict, the king magnanimously decided to renounce violence, to replace the misery caused by war with respect and dignity for all humanity. He propagated the faith by building

stupas and pillars urging, amongst other things, respect of all animal life and enjoining people to follow the

Dharma. Perhaps the finest example of these is the

Great Stupa of Sanchi, (near Bhopal, India). It was constructed in the 3rd century BC and later enlarged. Its carved gates, called

toranas, are considered among the finest examples of Buddhist art in India. He also built roads, hospitals, resthouses, universities and

irrigation systems around the country. He treated his subjects as equals regardless of their religion, politics or

caste.

This period marks the first spread of Buddhism beyond India to other countries. According to the plates and pillars left by Aśoka (the

edicts of Aśoka), emissaries were sent to various countries in order to spread Buddhism, as far south as

Sri Lanka and as far west as the Greek kingdoms, in particular the neighboring

Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, and possibly even farther to the Mediterranean.

3rd Buddhist council (c. 250 BC)[edit]

King

Aśoka convened the third Buddhist council around 250 BC at Pataliputra (today's

Patna). It was held by the monk

Moggaliputtatissa. The objective of the council was to purify the Saṅgha, particularly from non-Buddhist ascetics who had been attracted by the royal patronage. Following the council, Buddhist missionaries were dispatched throughout the known world.

Hellenistic world[edit]

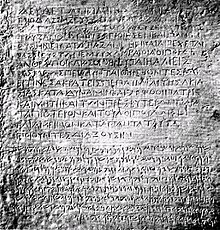

Some of the

edicts of Aśoka describe the efforts made by him to propagate the Buddhist faith throughout the Hellenistic world, which at that time formed an uninterrupted continuum from the borders of India to Greece. The edicts indicate a clear understanding of the political organization in Hellenistic territories: the names and locations of the main Greek monarchs of the time are identified, and they are claimed as recipients of Buddhist

proselytism:

Antiochus II Theos of the

Seleucid Kingdom (261–246 BC),

Ptolemy II Philadelphos of Egypt (285–247 BC),

Antigonus Gonatas of Macedonia (276–239 BC),

Magas (288–258 BC) in

Cyrenaica (modern

Libya), and

Alexander II (272–255 BC) in

Epirus (modern Northwestern

Greece).

- "The conquest by Dharma has been won here, on the borders, and even six hundred yojanas (5,400–9,600 km) away, where the Greek king Antiochos rules, beyond there where the four kings named Ptolemy, Antigonos, Magas and Alexander rule, likewise in the south among the Cholas, the Pandyas, and as far as Tamraparni (Sri Lanka)." (Edicts of Aśoka, 13th Rock Edict, S. Dhammika).

Furthermore, according to

Pāli sources, some of Aśoka's emissaries were Greek Buddhist monks, indicating close religious exchanges between the two cultures:

- "When the thera (elder) Moggaliputta, the illuminator of the religion of the Conqueror (Aśoka), had brought the (third) council to an end (...) he sent forth theras, one here and one there: (...) and to Aparantaka (the "Western countries" corresponding to Gujarat and Sindh) he sent the Greek (Yona) named Dhammarakkhita". (Mahavamsa XII).

Aśoka also issued edicts in the Greek language as well as in Aramaic. One of them, found in Kandahar, advocates the adoption of "piety" (using the Greek term

eusebeia for

Dharma) to the Greek community:

- "Ten years (of reign) having been completed, King Piodasses (Aśoka) made known (the doctrine of) piety (Greek:εὐσέβεια, eusebeia) to men; and from this moment he has made men more pious, and everything thrives throughout the whole world."

- (Trans. from the Greek original by G.P. Carratelli[6])

It is not clear how much these interactions may have been influential, but some authors

[citation needed] have commented that some level of

syncretism between Hellenist thought and Buddhism may have started in Hellenic lands at that time. They have pointed to the presence of Buddhist communities in the Hellenistic world around that period, in particular in

Alexandria (mentioned by

Clement of Alexandria), and to the pre-Christian monastic order of the

Therapeutae (possibly a deformation of the Pāli word "

Theravāda"

[7]), who may have "almost entirely drawn (its) inspiration from the teaching and practices of Buddhist asceticism"

[8] and may even have been descendants of Aśoka's emissaries to the West.

[9] The philosopher

Hegesias of Cyrene, from the city of

Cyrene where

Magas of Cyrene ruled, is sometimes thought to have been influenced by the teachings of Aśoka's Buddhist missionaries.

[10]

Buddhist gravestones from the

Ptolemaic period have also been found in Alexandria, decorated with depictions of the Dharma wheel.

[11] The presence of Buddhists in Alexandria has even drawn the conclusion: "It was later in this very place that some of the most active centers of Christianity were established".

[12]- "Thus philosophy, a thing of the highest utility, flourished in antiquity among the barbarians, shedding its light over the nations. And afterwards it came to Greece. First in its ranks were the prophets of the Egyptians; and the Chaldeans among the Assyrians; and the Druids among the Gauls; and the śramanas among the Bactrians ("Σαρμαναίοι Βάκτρων"); and the philosophers of the Celts; and the Magi of the Persians, who foretold the Saviour's birth, and came into the land of Judea guided by a star. The Indian gymnosophists are also in the number, and the other barbarian philosophers. And of these there are two classes, some of them called śramanas ("Σαρμάναι"), and others Brahmins ("Βραφμαναι")." Clement of Alexandria "The Stromata, or Miscellanies" Book I, Chapter XV[13]

Expansion to Sri Lanka and Burma[edit]

Sri Lanka was proselytized by Aśoka's son

Mahinda and six companions during the 2nd century BC. They converted the King Devanampiya Tissa and many of the nobility. In addition, Aśoka's daughter, Saṅghamitta also established the bhikkhunī (order for nuns) in Sri Lanka, also bringing with her a sapling of the sacred bodhi tree that was subsequently planted in Anuradhapura. This is when the

Mahāvihāra monastery, a center of Sinhalese orthodoxy, was built. The

Pāli canon was written down in Sri Lanka during the reign of king Vattagamani (29–17 BC), and the Theravāda tradition flourished there. Later some great commentators worked there, such as

Buddhaghoṣa (4th–5th century) and Dhammapāla (5th–6th century), and they systemised the traditional commentaries that had been handed down. Although Mahāyāna Buddhism gained some influence in Sri Lanka at that time, the Theravāda ultimately prevailed and Sri Lanka turned out to be the last stronghold of it. From there it would expand again to South-East Asia from the 11th century.

In the areas east of the Indian subcontinent (modern

Burma and

Thailand), Indian culture strongly influenced the

Mons. The Mons are said to have been converted to Buddhism from the 3rd century BC under the proselytizing of the Indian Emperor

Aśoka, before the fission between Mahāyāna and

Hinayāna Buddhism. Early Mon

[citation needed] Buddhist temples, such as Peikthano in central Burma, have been dated to between the 1st and the 5th century CE.

The

Buddhist art of the Mons was especially influenced by the Indian art of the

Gupta and post-Gupta periods, and their mannerist style spread widely in South-East Asia following the expansion of the Mon kingdom between the 5th and 8th centuries. The Theravāda faith expanded in the northern parts of Southeast Asia under Mon influence, until it was progressively displaced by Mahāyāna Buddhism from around the 6th century AD.

Rise of the Shunga (2nd–1st century BC)[edit]

The

Shunga dynasty (185–73 BC) was established in 185 BC, about 50 years after Aśoka's death. After assassinating King

Brhadrata (last of the

Mauryan rulers), military commander-in-chief

Pushyamitra Shunga took the throne. Buddhist religious scriptures such as the

Aśokāvadāna allege that Pushyamitra (an orthodox

Brahmin) was hostile towards Buddhists and persecuted the Buddhist faith. Buddhists wrote that he "destroyed hundreds of monasteries and killed hundreds of thousands of innocent Monks":

[14] 840,000 Buddhist

stupas which had been built by Aśoka were destroyed, and 100 gold coins were offered for the head of each Buddhist monk.

[15] In addition, Buddhist sources allege that a large number of Buddhist monasteries (

vihāras) were converted to

Hindu temples, in places like, but not limited to,

Nalanda,

Bodhgaya,

Sarnath, and

Mathura, among many others.

Modern historians, however, dispute this view in the light of literary and archaeological evidence. They opine that following Aśoka's sponsorship of Buddhism, it is possible that Buddhist institutions fell on harder times under the Shungas, but no evidence of active persecution has been noted.

Etienne Lamotte observes:

"To judge from the documents, Pushyamitra must be acquitted through lack of proof."[16] Another eminent historian,

Romila Thaparpoints to archaeological evidence that "suggests the contrary" to the claim that "Pushyamitra was a fanatical anti-Buddhist" and that he "never actually destroyed 840,000 stupas as claimed by Buddhist works, if any". Thapar stresses that Buddhist accounts are probably hyperbolic renditions of Pushyamitra's attack of the Mauryas, and merely reflect the desperate frustration of the Buddhist religious figures in the face of the possibly irreversible decline in the importance of their religion under the Shungas.

[17]

During the period, Buddhist monks deserted the

Ganges valley, following either the northern road (

uttarapatha) or the southern road (

dakṣinapatha).

[18]Conversely, Buddhist artistic creation stopped in the old

Magadha area, to reposition itself either in the northwest area of

Gandhāra and

Mathura or in the southeast around

Amaravati. Some artistic activity also occurred in central India, as in

Bhārhut, to which the Shungas may or may not have contributed.

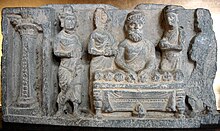

Greco-Buddhist interaction (2nd century BC–1st century AD)[edit]

The

Greco-Bactrian king

Demetrius I invaded the Indian Subcontinent in 180 BC, establishing an

Indo-Greek kingdom that was to last in parts of Northwest South Asia until the end of the 1st century CE. Buddhism flourished under the Indo-Greek and Greco-Bactrian kings, and it has been suggested that their invasion of India was intended to show their support for the

Mauryan empire and to protect the Buddhist faith from the alleged religious persecutions of the

Shungas (185–73 BC).

One of the most famous Indo-Greek kings is

Menander (reigned c. 160–135 BC). He converted to Buddhism and is presented in the Mahāyāna tradition as one of the great benefactors of the faith, on a par with king Aśoka or the later Kushan king

Kaniśka. Menander's coins bear the mention of the "saviour king" in Greek; some bear designs of the eight-spoked wheel. Direct cultural exchange is also suggested by the dialogue of the

Milinda Pañha around 160 BC between

Menander and the Buddhist monk

Nāgasena, who was himself a student of the Greek Buddhist monk

Mahadharmaraksita. Upon Menander's death, the honor of sharing his remains was claimed by the cities under his rule, and they were enshrined in

stupas, in a parallel with the historic Buddha.

[19] Several of Menander's

Indo-Greeksuccessors inscribed "Follower of the Dharma," in the

Kharoṣṭhī script, on their coins, and depicted themselves or their divinities forming the

vitarka mudrā.

It is also around the time of initial Greek and Buddhist interaction that the first

anthropomorphic representations of the Buddha are found, often in realistic

Greco-Buddhist style. The former reluctance towards anthropomorphic representations of the Buddha, and the sophisticated development of aniconic symbols to avoid it (even in narrative scenes where other human figures would appear), seem to be connected to one of the Buddha’s sayings, reported in the

Digha Nikaya, that discouraged representations of himself after the extinction of his body.

[20] Probably not feeling bound by these restrictions, and because of "their cult of form, the Greeks were the first to attempt a sculptural representation of the Buddha".

[21][page needed] In many parts of the Ancient World, the Greeks did develop

syncretic divinities, that could become a common religious focus for populations with different traditions: a well-known example is the syncretic God

Sarapis, introduced by

Ptolemy I in

Egypt, which combined aspects of Greek and Egyptian Gods. In India as well, it was only natural for the Greeks to create a single common divinity by combining the image of a Greek God-King (The Sun-God

Apollo, or possibly the deified founder of the

Indo-Greek Kingdom,

Demetrius), with the traditional

attributes of the Buddha. Many of the stylistic elements in the representations of the Buddha point to Greek influence: the

Greco-Roman toga-like wavy robe covering both shoulders (more exactly, its lighter version, the Greek

himation), the

contrappostostance of the upright figures (see: 1st–2nd century Gandhara standing Buddhas

[22]), the stylicized

Mediterranean curly hair and topknot (

ushnisha) apparently derived from the style of the

Belvedere Apollo (330 BCE),

[23] and the measured quality of the faces, all rendered with strong artistic

realism (See:

Greek art). A large quantity of

sculpturescombining Buddhist and purely Hellenistic styles and

iconography were excavated at the

Gandharan site of

Hadda.

Central Asian expansion[edit]

A Buddhist gold coin from India was found in northern

Afghanistan at the archaeological site of

Tillia Tepe, and dated to the 1st century AD. On the reverse, it depicts a lion in the moving position with a

nandipada in front of it, with the

Kharoṣṭhī legend "Sih[o] vigatabhay[o]" ("The lion who dispelled fear").

The Mahayana Buddhists symbolized Buddha with animals such as a lion, an elephant, a horse or a bull. A pair of feet was also used. The symbol called

nandipada by archaeologists and historians is actually a composite symbol. The symbol at the top symbolizes the "Middle Path", the Buddha

dhamma. The circle with a centre symbolizes

cakka. Thus, the composite symbol symbolizes

dhammacakka, the Buddhist Wheel of the Law. Thus, the symbols on the reverse of the coin jointly symbolize Buddha rolling the

dhammacakka. In the "Lion Capital" of Saranath, India, Buddha rolling the

dhammacakka is depicted on the wall of the cylinder with lion, elephant, horse and bull rolling the

dhammacakkas. On the obverse, an almost naked man only wearing an Hellenistic

chlamys and wearing a head-dress rolls a

dhammacakka. The legend in Kharoṣṭhī reads "Dharmacakrapravata[ko]" ("The one who turned the Wheel of the Law"). It has been suggested that this may be an early representation of the Buddha.

[25]

The head-dress symbolizes the "Middle Path". Thus, the man with the head-dress is a person who adheres to the Middle Path. (In one of the Indus Valley seals, we find a similar head-dress worn by 9 women.)

Thus, on both sides of the coin, we find Buddha rolling the dhammacakka.

As no scientific study on literary and physical symbolization of Buddha and Buddhism was conducted by the archaeologists and historians, imaginary and false interpretations were only given on coins, seals, Brahmi and other inscriptions and other archaeological finds.

Rise of Mahāyāna (1st century BC–2nd century AD)[edit]

Gold coin of Kanishka I with a representation of the Buddha (c.120 AD).

Obv: Kanishka standing, clad in heavy Kushan coat and long boots, flames emanating from shoulders, holding standard in his left hand, and making a sacrifice over an altar. Kushan-language legend in Greek script (with the addition of the Kushan Ϸ "sh" letter): ϷΑΟΝΑΝΟϷΑΟ ΚΑΝΗϷΚΙ ΚΟϷΑΝΟ ("Shaonanoshao Kanishki Koshano"): "King of Kings, Kanishka the Kushan".

Rev: Standing Buddha in Hellenistic style, forming the gesture of "no fear" (abhaya mudra) with his right hand, and holding a pleat of his robe in his left hand. Legend in Greek script: ΒΟΔΔΟ "Boddo", for the Buddha. Kanishka monogram (tamgha) to the right.

The earliest Mahāyāna sūtras to include the very first versions of the

Prajñāpāramitā genre, along with texts concerning

Akṣobhya Buddha, which were probably written down in the 1st century BCE in the south of India.

[29][30] Guang Xing states, "Several scholars have suggested that the Prajñāpāramitā probably developed among the Mahāsāṃghikas in southern India, in the Āndhra country, on the Kṛṣṇa River."

[31] A.K. Warder believes that "the Mahāyāna originated in the south of India and almost certainly in the Āndhra country."

[32]

Anthony Barber and Sree Padma note that "historians of Buddhist thought have been aware for quite some time that such pivotally important Mahayana Buddhist thinkers as

Nāgārjuna,

Dignaga,

Candrakīrti,

Āryadeva, and

Bhavaviveka, among many others, formulated their theories while living in Buddhist communities in Āndhra."

[33] They note that the ancient Buddhist sites in the lower Kṛṣṇa Valley, including

Amaravati,

Nāgārjunakoṇḍā and

Jaggayyapeṭa "can be traced to at least the third century BCE, if not earlier."

[34] Akira Hirakawa notes the "evidence suggests that many Early Mahayana scriptures originated in South India."

[35]

The Two Fourth Councils[edit]

The Fourth Council is said to have been convened in the reign of the

Kashmir emperor

Kaniṣka around 100 AD at Jalandhar or in Kashmir. Theravāda Buddhism had its own Fourth Council in Sri Lanka about 200 years earlier in which the Pāli canon was written down

in toto for the first time. Therefore, there were two Fourth Councils: one in Sri Lanka (Theravāda), and one in Kashmir (Sarvāstivādin).

Extent of Buddhism and trade routes in the 1st century AD.

It is said that for the Fourth Council of Kashmir, Kaniṣka gathered 500 monks headed by

Vasumitra, partly, it seems, to compile extensive commentaries on the

Abhidharma, although it is possible that some editorial work was carried out upon the existing canon itself. Allegedly during the council there were altogether three hundred thousand verses and over nine million statements compiled, and it took twelve years to complete. The main fruit of this council was the compilation of the vast commentary known as the Mahā-Vibhāshā ("Great Exegesis"), an extensive compendium and reference work on a portion of the Sarvāstivādin Abhidharma.

Scholars believe that it was also around this time that a significant change was made in the language of the Sarvāstivādin canon, by converting an earlier

Prakrit version into

Sanskrit. Although this change was probably effected without significant loss of integrity to the canon, this event was of particular significance since Sanskrit was the sacred language of

Brahmanism in India, and was also being used by other thinkers, regardless of their specific religious or philosophical allegiance, thus enabling a far wider audience to gain access to Buddhist ideas and practices. For this reason there was a growing tendency among Buddhist scholars in India thereafter to write their commentaries and treatises in Sanskrit. Many of the early schools, however, such as Theravāda, never switched to Sanskrit, partly because Buddha explicitly forbade translation of his discourses into what was an elitist religious language (as

Latin was in medieval Europe). He wanted his monks to use a local language instead - a language which could be understood by all. Over time, however, the language of the Theravādin scriptures (

Pāli) became a scholarly or elitist language as well, exactly opposite to what the Buddha had explicitly commanded.

Mahāyāna expansion (AD 1st–10th century)[edit]

Expansion of Mahāyāna Buddhism between the 1st and 10th centuries AD.

From that point on, and in the space of a few centuries, Mahāyāna was to flourish and spread in the East from India to

South-East Asia, and towards the north to

Central Asia,

China,

Korea, and finally to

Japan in 538 AD and

Tibet in the 7th century.

After the end of the

Kushans, Buddhism flourished in India during the dynasty of the

Guptas (4th-6th century). Mahāyāna centers of learning were established, especially at

Nālandā in north-eastern India, which was to become the largest and most influential Buddhist university for many centuries, with famous teachers such as

Nāgārjuna. The influence of the Gupta style of

Buddhist art spread along with the faith from south-east Asia to China.

Indian Buddhism had weakened in the 6th century following the

White Hun invasions and

Mihirakula's persecution.

Xuanzang reported in his travels across India during the 7th century, of Buddhism being popular in

Andhra,

Dhanyakataka and

Dravida, which area today roughly corresponds to the modern day Indian states of

Andhra Pradesh and

Tamil Nadu.

[36] While reporting many deserted stupas in the area around modern day

Nepal and the persecution of Buddhists by

Shashanka in the Kingdom of

Gauda in modern-day West Bengal,

Xuanzangcomplimented the patronage of

Harṣavardana during the same period. After the Harṣavardana kingdom, the rise of many small kingdoms that led to the rise of the

Rajputs across the gangetic plains and marked the end of Buddhist ruling clans along with a sharp decline in royal patronage until a revival under the

Pāla Empire in the

Bengal region. Here Mahāyāna Buddhism flourished and spread to

Tibet,

Bhutan and

Sikkim between the 7th and the 12th centuries before the Pālas collapsed under the assault of the Hindu

Sena dynasty. The Pālas created many temples and a distinctive school of Buddhist art.

Xuanzang noted in his travels that in various regions

Buddhism was giving way to

Jainism and

Hinduism.

[37] By the 10th century Buddhism had experienced a sharp decline beyond the Pāla realms in Bengal under a resurgent Hinduism and the incorporation in

Vaishnavite Hinduism of Buddha as the 9th incarnation of

Vishnu.

[38]

A milestone in the decline of Indian Buddhism in the North occurred in 1193 when

Turkic Islamic raiders under

Muhammad Khilji burnt Nālandā. By the end of the 12th century, following the Islamic conquest of the Buddhist strongholds in

Bihar and the loss of political support coupled with social pressures, the practice of Buddhism retreated to the Himalayan foothills in the North and

Sri Lanka in the south. Additionally, the influence of Buddhism also waned due to Hinduism's revival movements such as

Advaita, the rise of the

bhakti movement and the missionary work of

Sufis.

Central and Northern Asia[edit]

Central Asia[edit]

Central Asia had been influenced by Buddhism probably almost since the time of the Buddha. According to a legend preserved in

Pāli, the language of the Theravādin canon, two merchant brothers from Bactria named Tapassu and Bhallika visited the Buddha and became his disciples. They then returned to Bactria and built temples to the Buddha.

Central Asia long played the role of a meeting place between

China,

India and

Persia. During the 2nd century BC, the expansion of the

Former Han to the west brought them into contact with the Hellenistic civilizations of Asia, especially the

Greco-Bactrian Kingdoms. Thereafter, the expansion of

Buddhismto the north led to the formation of Buddhist communities and even Buddhist kingdoms in the oases of Central Asia. Some

Silk Road cities consisted almost entirely of Buddhist stupas and monasteries, and it seems that one of their main objectives was to welcome and service travelers between east and west.

The Theravādin traditions first spread among the

Iranian tribes before combining with the Mahāyāna forms during the 2nd and 3rd centuries BC to cover modern-day

Pakistan,

Kashmir,

Afghanistan,

Uzbekistan,

Turkmenistan and

Tajikistan. Various

Nikāya schools persisted in Central Asia and China until around the 7th century AD. Mahāyāna started to become dominant during the period, but since the faith had not developed a Nikaya approach,

Sarvāstivādins and

Dharmaguptakas remained the Vinayas of choice in Central Asian monasteries.

Parthia[edit]

Buddhism expanded westward into the easternmost fringes of

Arsacid Parthia, to the area of

Merv, in ancient

Margiana, today's territory of

Turkmenistan. Soviet archeological teams have excavated in Giaur Kala near Merv a Buddhist chapel, a gigantic Buddha statue and a monastery.

Parthians were directly involved in the propagation of Buddhism:

An Shigao (c. 148 AD), a Parthian prince, went to China, and is the first known translator of Buddhist scriptures into Chinese.

Tarim Basin[edit]

The eastern part of central Asia (

Chinese Turkestan,

Tarim Basin,

Xinjiang) has revealed extremely rich Buddhist works of art (wall paintings and reliefs in numerous caves, portable paintings on canvas, sculpture, ritual objects), displaying multiple influences from Indian and Hellenistic cultures.

Serindian art is highly reminiscent of the Gandhāran style, and scriptures in the Gandhāri script

Kharoṣṭhī have been found.

Central Asians seem to have played a key role in the transmission of Buddhism to the East. The first translators of Buddhists scriptures into Chinese were

Parthian (Ch: Anxi) like

An Shigao (c. 148 AD) or

An Hsuan,

Kushan of

Yuezhi ethnicity like

Lokaksema (c. 178 AD),

Zhi Qian and

Zhi Yao or

Sogdians like Kang Sengkai. Thirty-seven early translators of Buddhist texts are known, and the majority of them have been identified as Central Asians.

Central Asian and East Asian Buddhist monks appear to have maintained strong exchanges until around the 10th century, as shown by frescoes from the Tarim Basin.

These influences were rapidly absorbed, however, by the vigorous Chinese culture, and a strongly Chinese particularism develops from that point.

According to traditional accounts, Buddhism was introduced in China during the

Han dynasty (206 BC-220 AD) after an emperor dreamed of a flying golden man thought to be the Buddha. Although the archaeological record confirms that Buddhism was introduced sometime during the Han dynasty, it did not flourish in China until the Six Dynasties period (220-589 AD).

[42]

The year 67 AD saw Buddhism's official introduction to China with the coming of the two monks

Moton and

Chufarlan. In 68 AD, under imperial patronage, they established the

White Horse Temple (白馬寺), which still exists today, close to the imperial capital at

Luoyang. By the end of the 2nd century, a prosperous community had settled at Pengcheng (modern

Xuzhou,

Jiangsu).

The first known Mahāyāna scriptural texts are translations into Chinese by the Kushan monk Lokakṣema in Luoyang, between 178 and 189 AD. Some of the earliest known Buddhist artifacts found in China are small statues on "money trees", dated c. 200 AD, in typical Gandhāran drawing style: "That the imported images accompanying the newly arrived doctrine came from Gandhāra is strongly suggested by such early Gandhāra characteristics on this "money tree" Buddha as the high uṣniṣa, vertical arrangement of the hair, moustache, symmetrically looped robe and parallel incisions for the folds of the arms."

[43]

In the period between 460-525 AD during the

Northern Wei dynasty, the Chinese constructed

Yungang Grottoes, and it's an outstanding example of the Chinese stone carvings from the 5th and 6th centuries. All together the site is composed of 252 grottoes with more than 51,000 Buddha statues and statuettes.

Another famous Buddhism Grottoes is

Longmen Grottoes which started with the Northern Wei Dynasty in 493 AD. There are as many as 100,000 statues within the 1,400 caves, ranging from an 1 inch (25 mm) to 57 feet (17 m) in height. The area also contains nearly 2,500 stelae and inscriptions, whence the name "Forest of Ancient Stelae", as well as over sixty Buddhist pagodas.

Buddhism flourished during the beginning of the

Tang Dynasty (618–907). The dynasty was initially characterized by a strong openness to foreign influences and renewed exchanges with Indian culture due to the numerous travels of Chinese Buddhist monks to India from the 4th to the 11th centuries. The Tang capital of

Chang'an (today's

Xi'an) became an important center for Buddhist thought. From there Buddhism spread to

Korea, and Japanese embassies of Kentoshi helped gain footholds in Japan.

However, foreign influences came to be negatively perceived towards the end of the Tang Dynasty. In the year 845, the Tang emperor

Wuzong outlawed all "foreign" religions including Christian

Nestorianism,

Zoroastrianism, and

Buddhism in order to support the indigenous

Taoism. Throughout his territory, he confiscated Buddhist possessions, destroyed monasteries and temples, and executed Buddhist monks, ending Buddhism's cultural and intellectual dominance.

Pure Land and

Chan Buddhism, however, continued to prosper for some centuries, the latter giving rise to Japanese

Zen. In China, Chan flourished particularly under the

Song dynasty (1127–1279), when its monasteries were great centers of culture and learning.

Buddhism was introduced around 372 AD, when Chinese ambassadors visited the Korean kingdom of

Goguryeo, bringing scriptures and images. Buddhism prospered in Korea - in particular Seon (

Zen) Buddhism from the 7th century onward. However, with the beginning of the

Confucian Yi Dynasty of the

Joseon period in 1392, a strong discrimination took place against Buddhism until it was almost completely eradicated, except for a remaining Seon movement.

The Buddhism of Japan was introduced from

Three Kingdoms of Korea in the 6th century. The Chinese priest

Ganjinoffered the system of Vinaya to the Buddhism of Japan in 754. As a result, the Buddhism of Japan has developed rapidly.

Saichō and

Kūkai succeeded to a legitimate Buddhism from China in the 9th century.

Being geographically at the end of the

Silk Road, Japan was able to preserve many aspects of Buddhism at the very time it was disappearing in India, and being suppressed in Central Asia and China.

The Buddhism quickly became a national religion and thrived, particularly under

Shotoku Taishi (

Prince Shotoku) during

Asuka period (538-794). From 710, numerous temples and monasteries were built in the capital city of

Nara, such as the five-story

pagoda and Golden Hall of the

Hōryū-ji, or the

Kōfuku-ji temple. Countless paintings and sculptures were made, often under governmental sponsorship. The creations of Japanese Buddhist art were especially rich between the 8th and 13th centuries during

Nara period(710-794),

Heian period(794-1185) and

Kamakura period(1185-1333).

During

Kamakura period, major reformation activities started, namely changing from Buddhism for the imperial court to the Buddhism for the common people. The traditional Buddhism mostly focused on the protection of the country, imperial house or noble families from the ill spirits and salvation of the imperial families, nobles and monks themselves (self-salvation). On the other hand, new sects such as

Jodo shu (pure land sect) founded by

Honen and

Jodo Shinshu (true pure land sect) founded by

Shinran,

Honen's disciple, emphasized salvation of sinners, common men and women and even criminals such as murderers of parents.

Shinran preached the commoners by teaching that saying nembutsu (prayer of Amida Buddha) is a declaration of

faith in

Amida's salvation. Also for the first time in the history of Buddhism,

Shinran started a new sect allowing marriage of monks by initiating his own marriage, which was deemed as taboo from the traditional Buddhism.

Another development in

Kamakura period was

Zen, by the introduction of the faith by

Dogen and

Eisai upon their return from China. Zen is highly philosophical with simplified words reflecting deep thought, but, in the art history, it is mainly characterized by so-called zen art, original paintings (such as

ink wash and the

Enso) and poetry (especially

haikus), striving to express the true essence of the world through impressionistic and unadorned "non-dualistic" representations. The search for enlightenment "in the moment" also led to the development of other important derivative arts such as the

Chanoyu tea ceremony or the

Ikebana art of flower arrangement. This evolution went as far as considering almost any human activity as an art with a strong spiritual and aesthetic content, first and foremost in those activities related to combat techniques (

martial arts).

Buddhism remains active in Japan to this day. Around 80,000 Buddhist temples are preserved and regularly restored.

Buddhism arrived late in Tibet, during the 7th century. The form that predominated, via the south of Tibet, was a blend of

mahāyāna and

vajrayāna from the universities of the

Pāla empire of the Bengal region in eastern India.

[44] Sarvāstivādin influence came from the south west (Kashmir)

[45] and the north west (

Khotan).

[46] Although these practitioners did not succeed in maintaining a presence in Tibet, their texts found their way into the

Tibetan Buddhist canon, providing the Tibetans with almost all of their primary sources about the

Foundation Vehicle. A subsect of this school,

Mūlasarvāstivādawas the source of the Tibetan

Vinaya.

[47] Chan Buddhism was introduced via east Tibet from China and left its impression, but was rendered of lesser importance by early political events.

[48]

From the outset Buddhism was opposed by the native shamanistic

Bon religion, which had the support of the aristocracy, but with royal patronage it thrived to a peak under King Rälpachän (817-836). Terminology in translation was standardised around 825, enabling a translation methodology that was highly literal. Despite a reversal in Buddhist influence which began under King Langdarma (836-842), the following centuries saw a colossal effort in collecting available Indian sources, many of which are now extant only in Tibetan translation. Tibetan Buddhism was favored above other religions by the rulers of imperial Chinese and Mongol

Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368).

Southeast Asia[edit]

During the 1st century AD, the trade on the overland Silk Road tended to be restricted by the rise in the Middle-East of the

Parthian empire, an unvanquished enemy of

Rome, just as Romans were becoming extremely wealthy and their demand for Asian luxury was rising. This demand revived the sea connections between the Mediterranean and China, with India as the intermediary of choice. From that time, through trade connection, commercial settlements, and even political interventions, India started to strongly influence

Southeast Asian countries (excluding Vietnam). Trade routes linked India with southern

Burma, central and southern

Siam, islands of

Sumatra and

Java, lower

Cambodia and

Champa, and numerous urbanized coastal settlements were established there.

For more than a thousand years, Indian influence was therefore the major factor that brought a certain level of cultural unity to the various countries of the region. The

Pāli and

Sanskrit languages and the Indian script, together with Theravāda and Mahāyāna Buddhism,

Brahmanism, and

Hinduism, were transmitted from direct contact and through sacred texts and Indian literature such as the

Rāmāyaṇa and the

Mahābhārata.

From the 5th to the 13th centuries, South-East Asia had very powerful empires and became extremely active in Buddhist architectural and artistic creation. The main Buddhist influence now came directly by sea from the Indian subcontinent, so that these empires essentially followed the Mahāyāna faith. The

Sri Vijaya Empire to the south and the

Khmer Empireto the north competed for influence, and their art expressed the rich Mahāyāna pantheon of the

bodhisattvas.

Srivijayan Empire (7th–13th century)[edit]

Srivijaya, a maritime empire centered at

Palembang on the island of

Sumatra in

Indonesia, adopted Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna Buddhism under a line of rulers named the

Sailendras.

Yijing described Palembang as a great center of Buddhist learning where the emperor supported over a thousand monks at his court.

Yijing also testified to the importance of Buddhism as early as the year 671 and advised future Chinese pilgrims to spend a year or two in

Palembang.

[49] Atiśa studied there before travelling to

Tibet as a missionary.

As Srivijaya expanded their

thalassocracy, Buddhism thrived amongst its people. However, many did not practice pure Buddhism but a new syncretism form of Buddhism that incorporated several different religions such as Hinduism and other indigenous traditions.

[50]

Srivijaya spread

Buddhist art during its expansion in

Southeast Asia. Numerous statues of

bodhisattvas from this period are characterized by a very strong refinement and technical sophistication, and are found throughout the region. Extremely rich architectural remains are visible at the temple of

Borobudur the largest Buddhist structure in the world, built from around 780 in Java, which has 505 images of the seated Buddha. Srivijaya declined due to conflicts with the Hindu

Chola rulers of India, before being destabilized by the Islamic expansion from the 13th century.

Khmer Empire (9th–13th centuries)[edit]

Buddha from Preah Khan (Angkor), style post-bayon, 1250-1400, Musée Guimet, Paris.

Later, from the 9th to the 13th centuries, the Mahāyāna Buddhist and Hindu

Khmer Empire dominated much of the South-East Asian peninsula. Under the Khmer, more than 900 temples were built in Cambodia and in neighboring Thailand.

Angkor was at the center of this development, with a temple complex and urban organization able to support around one million urban dwellers. One of the greatest Khmer kings,

Jayavarman VII (1181–1219), built large Mahāyāna Buddhist structures at

Bayon and

Angkor Thom.

Vietnam[edit]

Buddhism in Vietnam as practiced by the Vietnamese is mainly of Mahāyāna tradition. Buddhism came from Vietnam as early as the 2nd century AD through the North from Central Asia via India. Vietnamese Buddhism is very similar to Chinese Buddhism and to some extent reflects the structure of Chinese Buddhism after the Song Dynasty. Vietnamese Buddhism also has a symbiotic relationship with Taoism, Chinese spirituality and the native Vietnamese religion.

Emergence of the Vajrayāna (5th century)[edit]

Various classes of Vajrayana literature developed as a result of royal courts sponsoring both Buddhism and

Saivism.

[51]The

Mañjusrimulakalpa, which later came to classified under

Kriyatantra, states that mantras taught in the Shaiva, Garuda and Vaishnava tantras will be effective if applied by Buddhists since they were all taught originally by

Manjushri.

[52] The Guhyasiddhi of Padmavajra, a work associated with the

Guhyasamaja tradition, prescribes acting as a Shaiva guru and initiating members into

Saiva Siddhanta scriptures and mandalas.

[53] The

Samvara tantra texts adopted the

pitha list from the Shaiva text

Tantrasadbhava, introducing a copying error where a deity was mistaken for a place.

[54]

Theravāda Renaissance (starting in the 11th century)[edit]

Expansion of Theravāda Buddhism from the 11th century.

From the 11th century, the destruction of Buddhism in the Indian mainland by Islamic invasions led to the decline of the Mahāyāna faith in South-East Asia. Continental routes through the Indian subcontinent being compromised, direct sea routes developed from the

Middle-East through

Sri Lanka to

China, leading to the adoption of the Theravāda Buddhism of the

Pāli canon, introduced to the region around the 11th century from

Sri Lanka.

King

Anawrahta (1044–1078); the founder of the

Pagan Empire, unified the country and adopted the Theravādin Buddhist faith. This initiated the creation of thousands of Buddhist temples at

Pagan, the capital, between the 11th and 13th centuries. Around 2,200 of them are still standing. The power of the Burmese waned with the rise of the

Thai, and with the seizure of the capital Pagan by the

Mongols in 1287, but Theravāda Buddhism remained the main Burmese faith to this day.

The Theravāda faith was also adopted by the newly founded ethnic

Thai kingdom of

Sukhothaiaround 1260. Theravāda Buddhism was further reinforced during the

Ayutthaya period (14th–18th century), becoming an integral part of Thai society.

In the continental areas, Theravāda Buddhism continued to expand into

Laos and

Cambodia in the 13th century. From the 14th century, however, on the coastal fringes and in the islands of south-east Asia, the influence of

Islam proved stronger, expanding into

Malaysia,

Indonesia, and most of the islands as far as the southern

Philippines.

Nevertheless, since

Suharto's rise to power in 1966, there has been a remarkable renaissance of Buddhism in Indonesia. This is partly due to the requirements of Suharto's New Order for the people of

Indonesia to adopt one of the five official religions:

Islam,

Protestantism,

Catholicism,

Hinduism or

Buddhism. Today it is estimated there are some 10 million Buddhists in Indonesia. A large part of them are people of Chinese ancestry.

Expansion of Buddhism to the West[edit]

After the Classical encounters between Buddhism and the West recorded in Greco-Buddhist art, information and legends about Buddhism seem to have reached the West sporadically. An account of Buddha's life was translated into

Greek by

John of Damascus, and widely circulated to

Christiansas the story of

Barlaam and

Josaphat. By the 14th century this story of Josaphat had become so popular that he was made a

Catholic saint.

The next direct encounter between Europeans and Buddhism happened in Medieval times when the

Franciscan friar

William of Rubruck was sent on an embassy to the

Mongol court of

Mongke by the French king

Saint Louis in 1253. The contact happened in Cailac (today's Qayaliq in

Kazakhstan), and William originally thought they were wayward Christians (Foltz, "Religions of the Silk Road").

In the period after

Hulagu, the Mongol

Ilkhans increasingly adopted Buddhism. Numerous Buddhist temples dotted the landscape of

Persia and

Iraq, none of which survived the 14th century. The Buddhist element of the Il-Khanate died with

Arghun.

[55]

The

Kalmyk Khanate was founded in the 17th century with Tibetan Buddhism as its main religion, following the earlier migration of the

Oirats from Dzungaria through

Central Asia to the steppe around the mouth of the

Volga River. During the course of the 18th century, they were absorbed by the Russian Empire.

[56] At the end of the

Napoleonic wars, Kalmyk cavalry units in Russian service entered

Paris.

[57]

Interest in Buddhism increased during the colonial era, when Western powers were in a position to witness the faith and its artistic manifestations in detail. The opening of

Japan in 1853 created a considerable interest in the arts and culture of Japan, and provided access to one of the most thriving Buddhist cultures in the world.

Buddhism started to enjoy a strong interest from the general population in the West following the turbulence of the 20th century. In the wake of the

1959 Tibetan uprising, a

Tibetan diaspora has made Tibetan Buddhism in particular more widely accessible to the rest of the world. It has since spread to many Western countries, where the tradition has gained popularity. Among its prominent exponents is the

14th Dalai Lama of Tibet. The number of its adherents is estimated to be between ten and twenty million.

[58]

See also[edit]